Kernel Games

The FreeBSD kernel can be dynamically tuned or changed on the fly, and most aspects of system performance can be adjusted as needed. We’ll discuss the kernel’s sysctl interface and how you can use it to alter a running kernel.

While some parts of kernel can be altered during the early stage of booting via boot loader.

FreeBSD has a modular kernel, meaning that entire chunks of the kernel can be loaded or unloaded from the OS, turning entire subsystem on/off as desired. Loading kernel modules can impact performance, system behavior, and hardware support.

What is the Kernel ?

The following definition is not complete, but will do people most of time, and its comprehensible : the kernel is the interface between the hardware and the software

The kernel lets software write data to disk drives and to the network. When a program wants memory, the kernel handles all low-level details of accessing the physical memory chip and allocates resources. Once mp3 passes codec software, kernel translate it into the stream of zeros and ones that your particular sound card understands. When a program requests CPU time, kernel schedules a time slot for it.

The way your kernel investigates some hardware during boot sequence defines how the hardware behaves, so you have to control that. Some devices identify them in a friendly manner, while other lock up if you ask them what they’re for.

The kernel and any modules included with FreeBSD are files in the directory /boot/kernel. Third-party kernel modules go in /boot/modules. Files elsewhere in the system are not part of kernel. Non kernel files are collectively called userland, meaning that they are intended for user even if they use kernel facilities.

Since kernel is just a set of files, you can use use alternate kernel for your special need.

Kernel State: sysctl

sysctl(8) allows you to peek at the values used by kernel and some cases lets you set them. These values are often referred to as sysctls.

Let’s start by grabbing all the sysctls in a file to view them easily.

sysctl -o -a > sysctl.out

A few of those values out of hundreds are

kern.hostname : storm

Most sysctls are meant to read this way but few are called opaque sysctls, can only be interpreted by userland programs. Show opaque sysctls with -o flag.

sysctl MIBs

The sysctls are organized in a tree format called as management information base(MIB) with several broad categories, such as net (network) ,kern, vm, etc.

- kern : Core kernel functions and features

- vm : Virtual Memory Sytem

- vfs : FileSystem

- net : Networking

- debug : Debugging

- machdep : Machine-dependent settings

- user : userland interface information

- p1003_1b : POSIX behavior

- kstat : Kernel Statistics

- dev : Device-specific information

- security : Security-specific kernel features

Each of above category is further divided. for e.g. Networking is divided into IP, ICMP, TCP and UDP.

sysctl Values and Definition

Each sysctl value is either a string, a integer, a binary value, or a opaque. All MIB’s are not well documented yet ! Some have obvious meaning e.g. kern.bootfile: /boot/kernel/kernel

But you can use this command to print the brief description of MIB.

sysctl -d kern.maxfilesperproc

Viewing sysctls

sysctl kern

List all element of kern MIB tree.

Changing sysctls

Some sysctls are read only. For example hardware MIBs.

hw.model: Intel(R) Xeon(R) CPU E5-1620 v2 @ 3.70 GHz

other example

vfs.usermount: 0 : this setting controls whether user can mount removable media.

now to change it

systctl vfs.usermount=1

Setting sysctls Automatically

we user /etc/sysctl.conf for persist the changes we have made for each boot.

The Kernel Environment

The Kernel is a program started by boot loader. Boot loader hands out the environment variables to kernel, creating the kernel environment. Kernel environment is also a MIB tree.

Viewing the Kernel Environment

kenv(8) : is used to view the kernel environment.

These variables look an awful lot like the loader variables. Because they are loader variables. They frequently relate to initial hardware probes.

These environment settings are also called boot-time tunable sysctls, or tunables, frequently related to low-level hardware settings.

Dropping Hints to Device Drivers

You can use environment variables to tell device drivers needed settings. Additionally, much ancient hardware requires the kernel to address it at very specific IRQ and memory values.

Kernel Modules

Kernel modules are part of a kernel that can be started or loaded, when needed and loaded when unused. Kernel modules can be loaded when you plug in a hardware and removed with that hardware. This expands system’s flexibility. Plus, a kernel with all possible functions compiled into it would be rather large.

Just as the default kernel is held in file /boot/kernel/kernel, kernel modules are the other files under /boot/kernel Each module name ends in .ko

Viewing Loaded Modules

The kldstat(8) command shows modules loaded into the kernel. You can check loaded submodules of each module using -v

Loading and Unloading Modules

there are 2 commands for that kldload and kldunload

kldload /boot/kernel/ipmi.ko

kldunload ipmi

Any active modules won’t be unloaded.

Loading Modules at Boot

Use /boot/loader.conf at load module at boot. Kernel load is almost same just remove .ko and add _load="YES".

procfs_load="YES"

Build Your Own Kernel

The kernel shipped in a default install is called GENERIC. GENERIC is configured to run on a wide variety of hardware although not necessarily optimally.

Preparation

You must have the kernel source code before you can build a kernel. If you followed my advice back in Chapter3, you are all set. If not, you can either go back into the installer and load the kernel sources, download the source code from a FreeBSD mirror, or jump ahead to Chap 18 and use svnlite(1).

You must have them in /usr/src.

Before building a new kernel, you must know what hardware your system has. The best way would be see the file /var/run/dmseg.boot.

Buses and Attachments

Every device in computer is attached to some other device. If you read your dmesg.boot carefully, you can see those chains of attachment.

acpi0: <SUPERM SMCI -- MB> on motherboard

acpi0: Power Button (fixed)

Our first device is acpi0 but note there is a power button on acpi0 device. The CPUs are also attached to acpi0, as is a timekeeping device.

Back Up your Working Kernel

The kernel install process keeps your previous kernel around all times. The kernel install process keeps your previous kernel around for backup purposes, in the directory /boot/kernel.old.

A common place to keep a know good kernel is /boot/kernel.good. If you are using ZFS, a boot environment might make more sense than copying.

Note : Hard Disk space is cheaper than time !! Configuration File Format

FreeBSD’s kernel is configured via text files. Each kernel configuration entry is on a single line. You’ll see a label to indicate what sort of entry this is, and then a term for the entry.

Many entries also have comments set off with a hash mark, much like for FreeBSD filesystem FFS.

options FFS # Berkeley Fast Filesystem

Every complete kernel configuration file is made up of five types of entries: cpu, indent, makeoptions, options and devices.

-

cpu : indicates what kind of processor this kernel supports.

-

ident: every kernel has this single line, giving a name for the kernel

-

makeoptions: string gives instruction to kernel-building software. most common options is DEBUG=-g, which tells compiler to build a debugging kerenl.

-

options: kernel functions that don’t require particular hardware. This includes filesystems, networking protocols, and in-kernel debuggers.

-

devices : Also known as device drivers, these provide the kernel with instructions on how to speak to certain devices. If you want your system to support a piece of hardware, the kernel must include the device driver for that hardware, but instead support whole categories of hardware like, Ethernet, random number generators, or memory disks. You might wonder what differentiate a pseudo device from an option, pseudo devices appear to the system as devices in at least some ways, while no device like features.

For example, loopback pseudodevice is a network interface that connects to only the local machine. While no hardware exists for it, software can connect to the loopback interface and send traffic to other software on the same machine.

Configuration Files

Fortunately, you won’t create kernel configuration file from search, instead you build on the GENERIC kernel for your hardware architecture. It can be found /sys/<arch>/conf

for example, the i386 kernel configuration files are in /sys/i386/conf, the amd64 kernel configuration files are in /sys/amd64/conf, and so on. This directory contains several files.

- DEFAULTS : This is a list of options and devices that are enabled by default for a given architecture. That doesn’t mean that you can compile and run DEFAULTS, but it is a starting point should you want to build a kernel by adding devices. Using GENERIC is easier, though.

- GENERIC : This is the configuration for the standard kernel. It contains all the settings needed to get standard hardware of that architecture up and running.

- GENERIC.hints : This is the hint file that is installed as

/boot/device.hints. This file provides configuration information for older hardware. - MINIMAL : This configuration excludes anything that can be loaded from a module.

- NOTES : This is an all-inclusive kernel configuration for that hardware platform. Every platform-specific feature is included in NOTES. Find platform-independent kernel feature in

/usr/src/sys/conf/NOTES

Building a Kernel

KERNCONF variable can be set in /etc/src.conf (or /etc/make.conf) to tell system which kernel configuration to build because all source code is already available in FreeBSD.

KERNCONF=MINIMAL

If you’re experiment with building and running different kernels, its best to set config file on command line when building kernel. Build the kernel with make buildkernel command.

cd /usr/src

make KERNCONF=MINIMAL buildkernel

Build process first runs config(8) to find syntactical configuration errors. If there are errors, it reports them and stops.

After building kernel, install it. Running make installkernel moves your current kernel to /boot/kernel.old and installs the new kernel in /boot/kernel. Installing a new kernel is faster than building it.

Once install completes, reboot your server and watch the boot messages. If everything goes fine you will see exactly what kernel is running and when it was built.

Note as name suggests MINIMAL kernel doesn’t boot on all hardware because it leaves everything that can be in module in a module. Disk partitions methods, both GPT and MBR, can be modules. You must load either geom_part_gpt.ko or geom_part_mbr.ko via boot loader to boot MINIMAL. You will need to this for every required piece of module !!

Booting an Alternate Kernel

You messed up things, but don’t worry carefully read all error messages and use the kernel in /boot/kernel.old and fix stuff slowly one by one or you can use the one in /boot/kernel.good. Reboot and interrupt the boot to get to the boot menu. The fifth option lets you choose a different kernel. The menu has kernel and kernel.old by default but we will need to add kernel.good

Once you install another new kernel, though, remember : the existing /boot/kernel gets copied to /boot/kernel.old . Note if you somehow end up having both of them not capable of booting :D stupid mistake xD thats why we need kernel.good.

Custom Kernel Configuration

Its easiest to modify existing configuration. You can already use already existing file or use include options.

Do NOT edit any of files in configuration directory directly. Instead, copy GENERIC to a file named after your machine of the kernel’s function and edit the copy. For ex we can make one for Virtual BOX and name it VBOX.

Trimming a Kernel

Earlier memory was more expensive than today, when system has 128MB of RAM, you want every bit of that to be available for work, not holding useless device drivers.

For most of us, stripping unnecessary drivers and features out of a kernel to shrink it is a waste of energy and time.

I boot up a working FreeBSD install on VirtualBox so I can get at dmesg.boot.

CPU Types

FreeBSD supports only one or two types of CPU. The amd64 platform only one, HAMMER. The i386 supports three, but two of those-the 486 and original Pentium-are wildly obsolete outside the embedded market.

cpu I486_CPU

cpu I586_CPU

cpu I686_CPU

We will include only one of them. check your cpu on dmesg.boot. Search for string that says 686-class, 486-class, etc . we can remove irrelevant statements.

Core Options

We have whole list of options for basic FreeBSD service, such as TCP/IP and filesystems. An average system won’t require all of these, but having them present provides a great deal of flexibility. But they are rarely used in your environment.

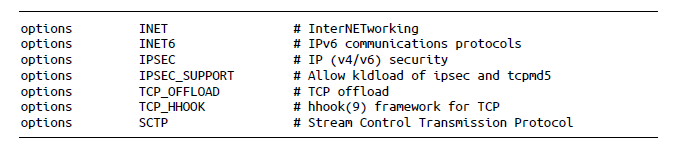

Consider these network options.

These options support networking. INET is the standard old TCP/IP, while INET6 supports IPv6. Much Unix-like software depend on TCP/IP, so you certainly require both of these. IPSEC and IPSEC_SUPPORT let you use IPSec VPN protocol. Those are not required on virtual machines.

The TCP_OFFLOAD options lets the network stack offload TCP/IP computation to network card. That sounds good except the vnet(4) network interfaces on virtual machines don’t perform that function. SO remove it.

TCP_HHOOK is convenient man page to read. We can keep it.

SCTP transport protocol is nifty, but totally useless to the virtual machines running on my laptop. Bye-Bye.

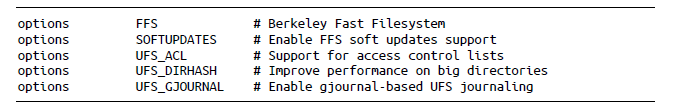

FFS provides standard FreeBSD filesystem, UFS. Even a ZFS host needs UFS support. The other options are all related to FFS.

SOFTUPDATES : ensures disk integrity even when the system shuts down incorrectly. UFS access lists allow you to grant detailed permissions on files, which is not needed on Virtual Host.

UFS_DIRHASH enables directory hashing, making directories with thousand of files more efficient. Keep that. And I’m going to use soft updates journaling, not gjournaling, so UFS_GJOURANAL can go away.

MD_ROOT : this option and other _ROOT options lets the system use something other than a standard UFS or ZFS filesystem as a disk device for root partition. The installer uses a memory device MD as a root partition.

If FreeBSD is running on a standard computer with hard drive and keyboard and whatnot, your kernel doesn’t need any of these features.

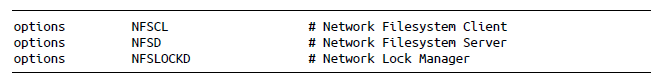

These options are related to Network File System.

We will include these.

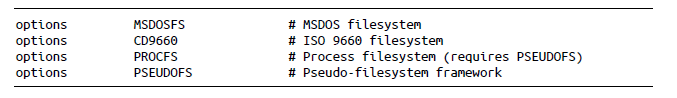

These adds bunch of important and useful FS. but note they are available as kernel modules too so you can remove them.

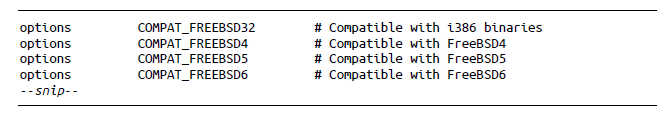

Very important compatibility options :D always include these

keep COMPAT_FREEBSD32 even if you don’t want backward compatibility, many software seem to rely on it.

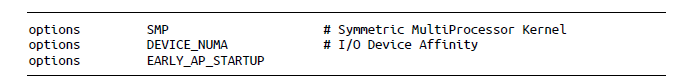

Multiple Processors

The following entries enable symmetric multiprocessing (SMP) in i386 kernels :

Device Drivers

After all the options, we will see the device driver entries, which are grouped in sensible way. To shrink kernel we can remove all the drivers host isn’t using but what host is using ? Search for each driver in dmseg.boot.

The first device entries are buses, such as device pci and device acpi. Keep these. Next, we read what most people consider device driver proper - entries for floppy drivers, SCSI controllers, RAID controllers, and so on. If your goal is to reduce kernel size , its a good place trim heavily.

Pseudodevices

These are created entirely out of software, hence the name. Some commonly used ones are.

device loop # Network loopback

A loopback device allows the system to communicate with itself via network sockets and network protocols.

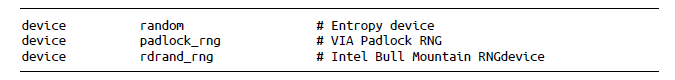

These devices are pseudorandom numbers generators, required for cryptography operations and such mission critical applications as games. FreeBSD supports a lot of randomness sources, and stores them in /dev/random/ and /dev/unrandom

device ether # Ethernet Support

Ethernet has many device-like characteristic, and it’s simplest for FreeBSD to treat it as a device. Leave this, unless you’re looking for learning opportunity.

Removable Hardware

The GENERIC kernel supports a few different sorts of removable hardware. If your laptop is not built in 99-00 then you don’t need that support in your kernel. FreeBSD supports hot-pluggable PCI cards, but if you don’t have them ? Throw these out.

Including the Configuration File

You kernel binary might be separated from the machine it’s built on. I recommend using INCLUDE_CONFIG_FILE options to copy kernel config into the compiled kernel.

Once you have your trimmed kernel, try to build it. Your first kernel configuration will invariably go wrong.

Troubleshooting Kernel Builds

If your kernel build fail, check the last lines of output. Some of these errors are quite cryptic, but others will be self-explanatory. Refer to section asking for help.

Fortunately, FreeBSD insists upon compiling a complete kernel before installing anything. A busted build won’t damage your installed system. It will however, give you an opportunity to test those troubleshooting skills we talked about way back.

Inclusion, Exclusions, and Expanding the Kernel

NOTES

FreeBSD’s kernel includes all sorts of features that aren’t included in GENERIC. Many of these special features are intended for very specific system or for weird corner cases of a special network.

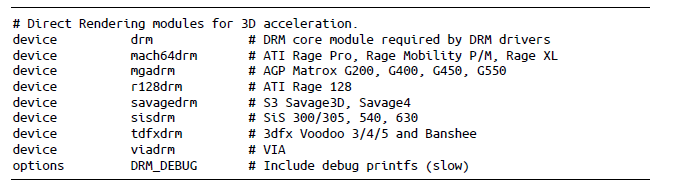

Are you using any of these video cards on your desktop ? Maybe you want a custom kernel that includes the appropriate device driver.

Always read NOTES every release or two, just to look for new interesting features.

Inclusions and Exclusions

FreeBSD’s kernel configuration has two interesting abilities that can make maintaining a kernel easier : the no option and the include feature.

include GENERIC

So, if you want to build a kernel that has all functionality of GENERIC but supports DRM features of VIA 3d chips, you can create a valid configuration composed entirely of following

ident VIADRM

include GENERIC

options DRM

options viadrm

do NOTE include is not best because when you upgrade FreeBSD, the GENERIC configuration can change.

Best way would be include all options from GENERIC then remove the options using nodevice or nooptions from it.

Take a look at GENERIC-NODEBUG configuration which is literally GENERIC except DEBUG options.

Skipping Modules

If you’ve gone to trouble of building a custom kernel, you probably know exactly which kernel host needs. Turn off building of modules in MODULES_OVERRIDE option. Set it to list of modules you want to build and install.

make MODULES_OVERRIDE='' kernel

you probably want to build most of modules but want to remove few.

make KERNCONFIG=VBOX WITHOUT_MODULE=vmm kernel